The use of the term “far-right” to describe political parties such as Reform UK is unhelpful. The term causes too visceral a reaction and at the same time is too broad to be meaningful. Tim Bale argues for a distinction between the “extreme right” and the “populist radical right” as more illuminating categories that can help us make sense of right-wing political parties.

On March 18th the BBC website’s Corrections and Clarifications page carried the following statement:

“In an article about the Liberal Democrats’ spring conference we wrongly described the political party Reform UK as far-right when referring to polling. This sentence was subsequently removed from the article as it fell short of our usual editorial standards. While the original wording was based on news agency copy, we take full responsibility and apologise for the error.”

The BBC’s statement apparently came about after the organisation was contacted by lawyers acting for the leader of Reform UK, Richard Tice. In his response on social media, Tice noted that the party was “also in touch with other news organisations” which had repeated a description that he views as “defamatory and libellous”. This may explain why, with the odd exception, few people seem to have pushed back on the corporation’s climbdown.

I’m no lawyer so I offer no opinion whatsoever on whether the BBC did or did not libel or defame Reform. But as a political scientist, I want to suggest that applying the term “far-right” to any particular party is probably a mistake – partly because the term is something of a “boo-word” and therefore inevitably more likely to generate more heat than light, but also because it is actually an umbrella term used to group a whole bunch of parties which, individually, can be more precisely (and arguably, therefore, more fruitfully) labelled.

It’s fair to say that there exists a degree of consensus that, when it comes to the right there are two important subtypes: the mainstream right and the far right.

Contested concepts are hardly uncommon in the social sciences. Scholars often disagree about the best way to define key notions that we routinely, almost unconsciously, employ to make sense of the political world. And given that there is already plenty of room for argument about what exactly we mean by the ‘descriptors “left” and “right”, it is hardly surprising that going beyond them to distinguish between subtypes – and then between subtypes of those subtypes – isn’t necessarily plain sailing. But that doesn’t mean it’s not worth doing.

In fact, it’s fair to say that there exists a degree of consensus that, when it comes to the right – or at least the right in Europe – there are two important subtypes: on the one hand, the mainstream right, and on the other hand, the far right. We can then distinguish specific party families within each of these two subtypes or umbrella terms. While the Christian democrats, the Conservatives and the Liberals are normally seen as examples of the mainstream right, the far right tends to be represented by parties of, on the one hand, the populist radical right and, on the other, the extreme right.

Mainstream right parties tend to be long-established players. Not only do they adopt relatively centrist and moderate programmatic positions, they also support existing norms and values traditionally associated with liberal, representative democracy, meaning they wouldn’t dream of calling, for instance, for the prevailing political system to be overturned, let alone overthrown.

By contrast, far right parties, tend to be newer entrants into the political system – “challengers”, “disruptors”, “insurgents”, call them what you will. And they almost instinctively adopt more obviously hard-core positions, as well as exhibiting weaker commitment to the formal and informal rules of the game that are intrinsic to (liberal) democratic regimes. Their critique of those regimes is sometimes explicit, even going so far as to countenance or at least tolerate violence – one reason, presumably, why the far-right label is seen as so toxic. But regime critique can often be rather more subtle, indicated, for example, by a questionable commitment to certain rules of the game such as respectful discourse or even basic civil, political, and minority rights.

The extreme right, often with its roots in fascism and/or the neo-Nazi underground, is characterised by the more explicit of the two approaches and, even when not openly undemocratic, it provokes suspicions that, were it ever to win power, free and fair elections, along with a whole bunch of democratic safeguards, would soon be scrapped.

The populist radical right, however, having no such heritage or else doing its best to claim (like the Austrian Freedom Party or the Sweden Democrats, for example) that it has transcended them, takes a more subtle approach, that includes a commitment to democracy. Just as importantly, it may (often with justification) be associated with nationalism and nativism that sometimes shades into outright xenophobia, believing that the needs and the interests of citizens should take priority over non-citizens – especially but not exclusively when it comes to, say, welfare or housing.

What really marks out the populist radical right is its populism – namely the distinction it makes, as Cas Mudde famously put it, between “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite”.

That said, the populist radical right, unlike the extreme right, does not (at least formally) trade in discrimination along ethnic and racial lines. Instead, it holds that, rather than one being inherently superior to another, different ethnicities, nationalities and (increasingly) religions are potentially incompatible and best off staying where they belong if they are unwilling or unable to integrate. Nor is radical right wing populism inherently authoritarian – at least in the common sense understanding of that word. Indeed, parties classified as such are often, if anything, libertarian, save when it comes to matters like migration and crime and punishment.

But what really marks out the populist radical right is its populism – namely the distinction it makes, as Cas Mudde famously put it, between “the pure people” (who are assumed to abound in ‘common sense’) and “the corrupt elite” and its tendency to prioritise popular sovereignty over liberal, representative democracy that, in its views, favours an out-of-touch, self-interested, and increasingly “woke” establishment bent on frustrating “the will of the people”.

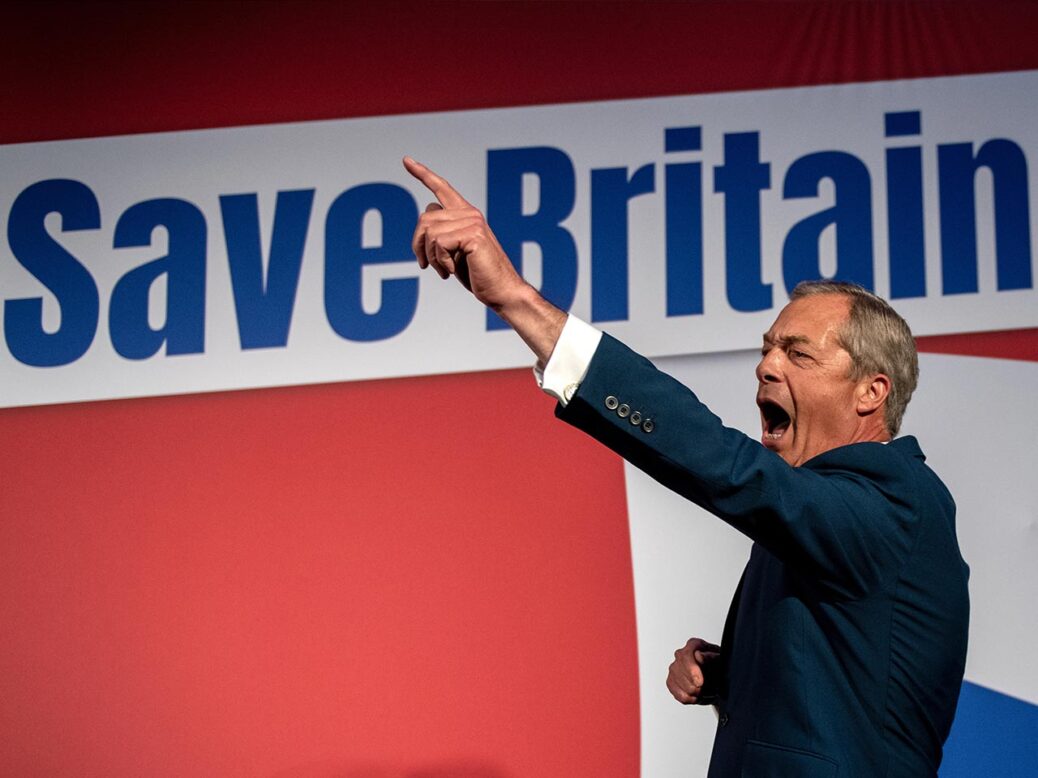

These features will be more than familiar to anyone who has listened to hard-core Brexiteers over the last decade or so. Whether, along with some of the other defining characteristics of the populist radical (as opposed to the extreme) right outlined above, it helps us – and perhaps even the BBC – more accurately describe Reform UK (and even perhaps some parts of the contemporary Conservative Party) I leave others to judge.

Source: LSE